Introduction

In 2025, the world’s major central banks and governments are orchestrating a dramatic shift in global financial markets. On one hand, the era of aggressive bond-buying programs—known as quantitative easing (QE)—is retreating as central banks attempt to normalize monetary policy. On the other, governments are flooding bond markets with new debt to cushion economies against the specter of recession. This dual move is upending bond markets worldwide: bond prices are falling, yields are climbing, and investors are left grappling with returns that often remain negative after inflation is factored in.

Central Banks Shift Gears: From QE to Quantitative Tightening

Since the 2008 crisis and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, central banks like the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank (ECB), and Bank of Japan (BOJ) used QE to keep borrowing costs low—buying trillions in government and sometimes corporate bonds. This unprecedented support suppressed yields and provided a backstop for markets.

But by 2025, the economic landscape is changing:

•Federal Reserve and ECB: Both have started to reduce their bond portfolios by letting assets mature or selling some holdings directly, significantly reducing demand for government paper.

•Bank of Japan: After years of massive stimulus, the BOJ has begun gradually tapering its bond purchases, now considering even slower reductions to avoid destabilizing markets.

The effect? A crucial anchor for bond prices is being removed, putting upward pressure on yields as buyers become more scarce and risk-aware.

Governments Ramp Up Debt to Counter Recession

Amid slowing growth and persistent political and economic uncertainty, governments are leaning heavily on fiscal stimulus to prevent or dampen recessions. The US, European economies, and others have significantly ramped up issuance of sovereign debt:

•New government bond issuance in OECD countries is projected to reach a record $17 trillion in 2025, smashing the $14 trillion issued just two years earlier.

•The US faces a daunting $9–10 trillion debt refinancing challenge this year, as much of its existing debt (30%) matures and needs to be rolled over at much higher rates.

•The UK, France, Germany, and Japan are similarly expanding their borrowing to meet their fiscal needs and cushion social systems, putting additional strain on bond markets.

With central banks now pulling back as buyers, these new bonds must find private investors willing to absorb the supply—typically at lower prices and higher yields.

What’s Happening to Bond Prices—and Yields?

As the supply of bonds increases and central banks become less eager buyers, market forces drive bond prices down and yields up:

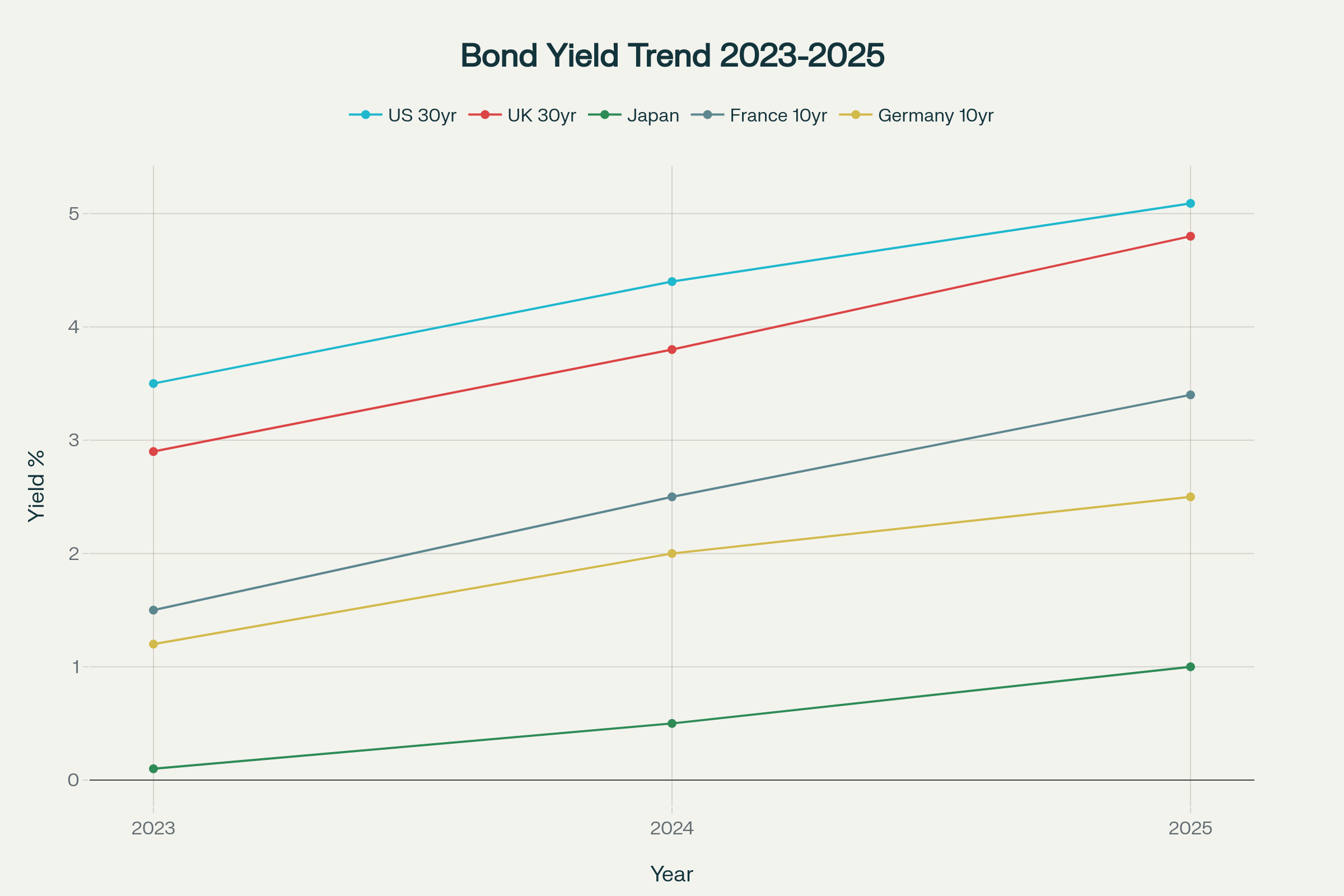

•US 10-year Treasury yields, for example, climbed from 3.6% in late 2024 to about 4.7% in mid-2025, with the 30-year yield topping 5.09%.

•UK 30-year gilt yields and Japanese 20-year bond yields have similarly reached heights not seen for decades.

•Yields in the eurozone’s core economies (France and Germany) have also climbed, pushing borrowing costs higher for governments.

•These increases persist even as base interest rates have started to come down, reflecting a significant shift in market sentiment.

Rising yields hurt existing bond holders, as prices fall, and raise borrowing costs for national treasuries.

Rising Bond Yields in Major Economies (2023-2025)

Inflation-Adjusted Yields: Still Below Water

Despite these nominal yield jumps, real yields—that is, yields after adjusting for inflation—often remain deeply negative or only marginally positive:

•US 10-year “real” yields (after subtracting inflation expectations) only recently turned positive and remain historically low compared to past tightening cycles.

•In Europe and Japan, persistent inflationary pressures mean that most government bonds still offer negative returns once adjusted for rising prices.

•Investors, therefore, face a paradox: they are demanding higher nominal yields to compensate for fiscal risk and inflation, but actual purchasing power remains stagnant or declines when holding many government bonds.

Why It Matters: Term Premiums, Fiscal Risks, and Economic Outlooks

The sharp rise in yields—especially on long-term bonds—reflects not just action by central banks, but also investor concerns:

•The term premium (extra return demanded to hold long bonds) is rising from historic lows as risks mount, but still hasn’t reached levels seen in previous debt crises or stagflation.

•High yields mean higher interest costs for governments, raising questions about fiscal sustainability and the risk of a future sovereign debt crisis.

•For investors, falling bond prices and volatile yields complicate traditional allocation models that rely on bonds as a source of stability.

Conclusion

The bond market reset of 2025 is the result of an unprecedented experiment in policy and an extraordinary fiscal response to economic shocks. As central banks step back and governments step forward, the interplay is shaping a new era of bond volatility, higher yields, and persistent real negative returns in some regions.

For policymakers, the dance between monetary withdrawal and fiscal expansion promises challenges—and perhaps more storms ahead.

References:

This article draws upon current financial market commentaries, official debt data, and research from Reuters, Morningstar, Economic Times, OECD, and others for 2025 market facts and figures